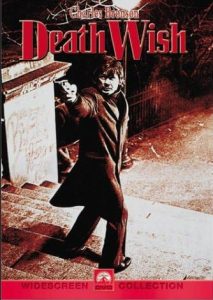

This is the one that started it all; Michael Winner’s 1974 classic that helped usher in an era of hostility to liberalism, minorities, and apologists for crime and violence. Without it, Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 would not have been possible. Sensing that the “Silent Majority” of Nixon’s America was reaching the boiling point, Winner gave us a film that mocked the notion that pacifism could ever hope to save us from the dark-skinned monsters storming the gates. Charles Bronson’s Paul Kersey is, at the beginning, a soft-spoken liberal who loves his wife and loves the Big Apple with every ounce of his bleeding heart. When we first meet Paul, he is relaxing on a vacation with his beautiful bride and the soundtrack informs us that this indeed is heaven on earth. Within minutes, Paul’s world is shattered and he is transformed into a hateful, trigger-happy killing machine who has left all remnants of passive liberalism behind. It doesn’t seem to matter that Paul never finds the people directly responsible for his wife’s murder and daughter’s rape, because in this world, it only matters that criminals are taken off the street. One no-good punk is as good as any other.

Whenever I revisit the first film of this series, I am always reminded how easily we could have been spared the final four installments. When Mrs. Kersey and her daughter decide to have their groceries delivered rather than grabbing the bags themselves (it should be noted that the groceries consist of no more than a box of cereal and perhaps two loaves of bread), it leaves an opportunity for a gang of killers (led by “Freak 1” Jeff Goldblum) to steal the address and pay the Kersey family a visit. Moments later, the thugs come calling, burst into the home, and savagely attack the two women. Mrs. Kersey is beaten to death (but not before hearing the classic line “I rape rich cunts like you”) and the daughter is forced to perform oral sex. She also suffers the indignity of having her ass spray-painted. The scene is quick and intense, and sets the stage for carnage unprecedented in film history.

Paul buries his wife, institutionalizes his daughter, and temporarily escapes to Arizona, where he meets a client who happens to be a gun nut. The man gives Kersey a going away present and with that gift, Kersey kills his first human being. At first Paul can only use a sock filled with quarters to wound his victims, but it doesn’t take long before he graduates to cold steel and hot lead. Paul walks the streets, rides the subway, and prowls about in the dark, all in the hopes of trapping poor young saps into committing a crime. Once attempted, the men are blown away without hesitation. Of course, the vigilante killings terrify the criminal population, reducing crime and embarrassing the NYPD. After all, if they admit that lone gunmen can bring down the crime rate, what need would there be for the thin blue line? At least this is the argument being put forth by the film. Such a belief is similar to the mantra “An armed society is a polite society,” and is based more in fear than any reliable statistics. Even though most right-wingers profess an admiration for the police, it is the stated purpose of this film to convince Americans that cops (and their superiors) have given up, given in, and have ceded control to the largely black and Hispanic criminals that rule the streets. Only white men armed to the teeth can save us, after all.

As such, Death Wish is the only overtly political film of the bunch, and it works (so to speak) as a straight drama. A storyline is at least attempted, and there is character “growth” as we watch Paul convert from left to right. And who couldn’t sympathize? After all, you don’t kill a man’s wife mere days after they share cocktails on the beaches of Hawaii. Winner and subsequent directors gave up after the first film and decided to shoot for pure exploitation, which was proper given that few things are as intolerable as a preachy action film. While the first film provides reasonable explanations for Paul’s violent outbursts, parts two through five give us a wind-up toy as a character who is let loose to butcher as many people as possible before the camera runs out of film. True, Paul loses a daughter, several good friends, and at least three lovers in the final four films, but it is clear that Paul doesn’t give a shit about any of them. Their deaths are mere excuses for Paul to load his weapons. But his first wife — so innocent and pure it seems — is a different story. Her death demanded vengeance of the highest order.